History

A Phoenician port in the Carraixet Ravine

Human settlement in the area that is now Alboraya dates back more than 2,000 years, from the Iberian and Roman eras to the present day. While no direct evidence of early human occupation has been found within Alboraya itself, studies of the surrounding region provide insight into how the territory evolved over time. However, when we focus on the past two millennia, our understanding becomes much clearer, particularly from the time of the Christian conquest of Islamic Valencia and the establishment of the Kingdom of Valencia—about 750 years ago.

To fully grasp how the original inhabitants lived, we must distinguish between population and settlement in an abstract sense, and Alboraya as a defined community. The birth of Alboraya as a community can be traced back to King James I and his donation of the Moorish farmsteads of Alboraya and Almàssera in 1238 to Bishop Vidal de Cañellas of Huesca. Before this point, the existence of these settlements is evident, but no concrete records describe them as a unified entity with any form of administrative structure. Therefore, we will refer separately to the population (the people who lived in the area) and the settlement (how they were physically distributed across the land).

Between the Carraixet ravine and the Palmar ravine, and from the northern Carraixet up to the Meliana ravine—this is the area we will define as Alboraya. Its eastern boundary is the sea, while to the west, it is bordered by the Via Augusta, now the Barcelona highway. At first glance, this may seem like a rather inhospitable place to settle, given the stagnant water, frequent flooding, and proximity to the sea (which brought the threat of corsairs and pirate attacks). It is within this context that we must place the founding of the city of Valentia in 138 BC. By then, Roman culture had begun to replace the Iberian way of life in the surrounding areas, as evidenced by settlements like Tos Pelat (between Montcada and Bétera) and El Puig in l’Horta Nord. The most important Iberian cities in a broader radius were Arse (modern-day Sagunt) and Edeta (Llíria), while in l’Horta Nord, according to studies by Josep Corell, traces of Roman inscriptions have been found in Paterna, Carpesa, Godella, Montcada, El Puig, and Puçol. The Via Augusta connected Valentia with Sagunt, running at a distance of about three kilometers from the coast at its closest point. Over time, settlements flourished along its path.

In 1997, archaeologist Rosa Albiach excavated a Roman-era cemetery in the Orriols area, near the Monastery of San Miguel de los Reyes. The site contained two funerary structures where multiple burials were discovered, along with ceramics and various objects made of gold, iron, lead, and bronze. The Romans typically built cemeteries outside their towns and villas, which suggests that this burial site could have belonged to the city itself or to one or more nearby villas. There are also indications of a path leading from this area toward what is now Alboraya (Albiach, 2005).

One aspect that gives us insight into the occupation of the region is the system of Roman-era land divisions known as centuriae. Some scholars, such as geographer Vicenç M. Rosselló, have argued that the origins of the Huerta can be traced back to the Romans based on this system. These centuriae were parcels of land granted to soldiers and their families as compensation for military service. Each unit, intended to sustain one hundred soldiers, covered an area of approximately 50 hectares, according to studies on the Roman plot in the region of l´Horta Nord by Segura Gomis and Roig Hurtado. These divisions were located near the Via Augusta and the Montcada irrigation canal, and thanks to land surveys, it has been determined that even after 2,000 years, the network has retained some of its original structure, particularly in terms of drainage systems and irrigation branches.

On the beaches of La Malvarrosa-Cabanyal, there was once an anchorage point that may date back to Phoenician times, as amphorae have been found in the area ranging from that period up until the 15th century. The mouth of the Carraixet offered ships an ideal spot to anchor near the shore and carry out loading and unloading operations, as the coastline here has a very gentle slope (according to studies by Segura Gomis and Roig Hurtado). Artifacts recovered from the site date back to Phoenician, Greek, Punic, Iberian, Etruscan, and Roman times, covering a period from the 7th century BC onward. However, it remains uncertain whether there was a settlement nearby in addition to the anchorage.

Some researchers have also attempted to prove that the Carraixet was once a navigable waterway reaching as far inland as Bétera or Montcada, potentially serving as a trade route with the Iberian settlements of Tos Pelat and others. What is clear is that the network formed by the Via Augusta to the west, the anchorage to the east, the centuriae to the north, and the cemetery to the south strongly suggests that the area corresponding to present-day Alboraya and its surroundings was inhabited during Roman times.

From this period onward, there is a historical silence regarding Alboraya that lasts until the 13th century. However, we can infer details about the Huerta and its population distribution during the Arab era through records such as the Llibre del Repartiment (Book of Land Grants) of James I, which documents the redistribution of Arab farmsteads (alquerías). The sheer number of these settlements suggests that the area was densely populated. Some place names of clear Arabic origin have also survived to this day. Carme Barceló provides the following meanings: Alboraya (“the little tower”); Rafelterràs, once a farmland storage site (“the estate of the broquerer- artisan shield maker”); Massamardà (“the inn or establishment of the Mardà family”). Other names include Almàssera (“oil mill”); Ruzafa (“the garden”); Albalat (“the road”); and Mauella (“hut” or “barraca”). The word acequia means “that which distributes water.” Meanwhile, the underground drainage channels used for irrigating fields are known in the region as encadufat.

The Creation of the Taifa of Valencia

From the 11th century onward, the city of Valencia and its surrounding territory had to be reorganized for defense (López Elum). During this time, the nearby villages (alquerías) were fortified, just like the city itself, forming a defensive network. In l’Horta Nord, the most important alquerías were Museros, Montcada, Paterna, and Quart. It is possible that Alboraya was also one of these fortified settlements, with its tower giving the town its name.

Throughout the 11th century, a series of defensive structures emerged—towers, walled enclosures, and albacaras (protected refuges)—shaping the landscape that the Christians would encounter upon their arrival in l’Horta in the mid-13th century. Some of these settlements had smaller alquerías under their protection, such as Museros, which controlled Massamagrell and the castle of El Puig.

King James I launched his campaign to capture Valencia between 1234 and 1238, first taking Montcada (where, according to his Chronicle, he captured over 1,100 prisoners), followed by Museros, El Puig, Paterna, Bétera, and Bofilla—each of these places had an estimated population of over 1,000 inhabitants. Once the king had established his base at la muntanyeta de La Patà- The Little Hill of La Patà- in El Puig, the Muslim population living between this point and the Turia River (López Elum), realizing they could not withstand the assault, retreated to Valencia. Shortly before the Christian conquest, in April 1238, the entire territory north of the city, including what is now Alboraya, was devastated.

Libro del Repartimiento (Book of Land Grants)

Written by King James I, this document records the donation of various properties in the alquería of Alboraya, as studied by Enric Climent. On February 25, Bernat Pesador, from Tortosa, was granted two yugadas of land- or plots of land- and a house; he also received the houses of Mahomat Abincalot and the orchard of Abdela Abenhoto (along with two more units of land). Ramon Bell-lloc was given seven yugadas; Joan Péreç de Gimon received two yugadas in Almàssera, one in Alboraya, and three fanegadas; while the Bishop of Huesca, Vidal de Canyelles, was granted the entire alquería or settlement of Alboraya. It goes without saying that these properties were taken from their original owners, who are also mentioned in the Llibre del Repartiment- Book of Grants, such as Mahomat Huarat Crepat and Maymo Habohachil Amançafi.

.jpg)

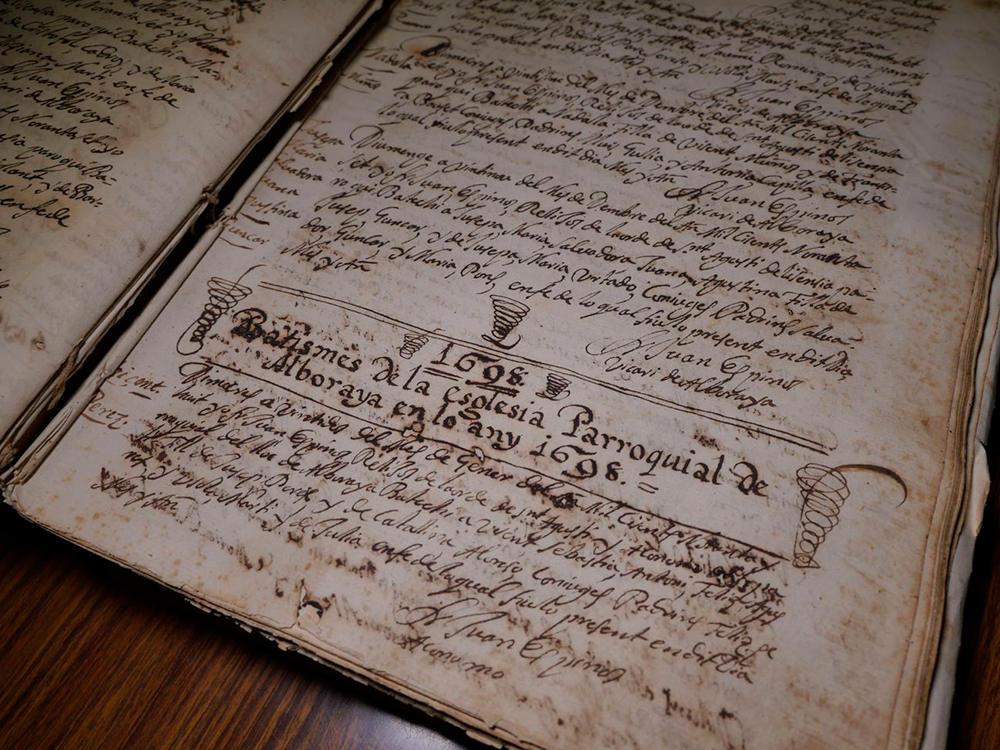

The Parish Church of Alboraya

Following the recognition of the alquería of Alboraya as the property of the Bishop of Huesca, the parish church of Alboraya was founded. This occurred on June 28, 1240, very shortly after the conquest, and the church was consecrated to the Assumption. The act of the parish church’s creation (Monrós Lliso) is recorded in the first Quinqui Libri (Book of Sacraments) preserved in the Alboraya Parish Church Archive, dating from the tenure of Rector Agustí Castillo (1596–1603).

After the bishop’s death, Alboraya and Almàssera became the property of James I’s third wife, Teresa Gil de Vidaure. Upon her passing, the estates were inherited by her children and later came into the possession of the Italian Della Volta family. A notarial document from 1290, in which the three Volta brothers formalized the division of two estates named Alboraya and Almàssera, confirms this transaction (Rojo Hurtado).

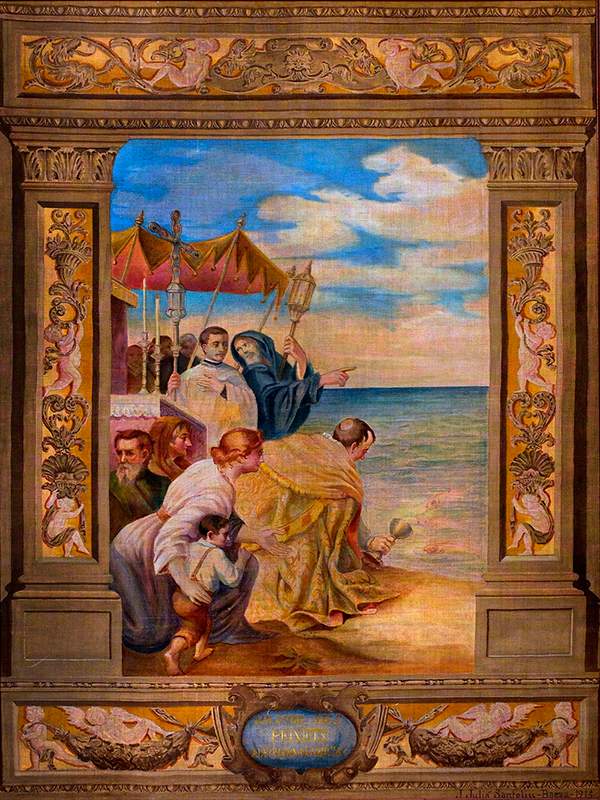

The Miracle of the Little Fish (El Miracle del Peixets)

The event that undoubtedly left the greatest mark on Alboraya’s medieval history is El Miracle dels Peixets (The Miracle of the Little Fish), which took place in 1348. According to tradition, the priest of Alboraya was carrying Communion to a Muslim convert in Almàssera when, while crossing the Carraixet ravine, the consecrated hosts fell into the water. The priest later recovered them at the river’s mouth, where they were miraculously held in the mouths of fish—three, according to the Alboraya version of the story, and two according to Almàssera’s, which is why the number varies depending on the storyteller’s origin.

This miracle has endured through time and remains deeply ingrained in the collective memory of both towns. In fact, it is the event that has received the most attention in the historical records of both communities. Later chronicles by Jaime Bleda, Gaspar Escolano, Marcos Antonio de Orellana, Josep Mariano Ortiz, and even 20th-century scholars such as Martínez Aloy and Listar all recount the event—though often with variations and embellishments. As a testament to this miracle, the Ermita dels Peixets chapel was built in 1907 at the very site where the fish returned the consecrated hosts to the priest. Today, there is also a vast body of literature dedicated to studying and analyzing the event. It is also worth noting that El Miracle dels Peixets marked the beginning of Almàssera’s push for ecclesiastical independence from Alboraya. This was initially granted during the time of Bishop Hug de Fenollet, with Almàssera becoming a perpetual vicarage in 1376—an event that some researchers consider the true beginning of Almàssera’s history as an independent municipality. A later ruling in 1645 reaffirmed this autonomy. The nearly 300 years that passed between these two milestones (as noted by Climent) led to ongoing disputes over territorial boundaries between the two communities. This longstanding ambiguity, rather than the number of fish in the legend, might better explain the historically strained relations between Alboraya and Almàssera.

Quinque Libri of the Parish of Alboraya

The Quinque Libri of the Parish of Alboraya contains several notes that provide insight into how the people of Alboraya celebrated Holy Week in the late 16th and early 17th centuries (Enric Climent, 2000). The priest of the Church of the Assumption until 1596, Vicent Herrero Esteve, wrote:

"Wax for the monument, candles for the torches, and incense. Likewise, each year, the churchwardens must give the rector or curate one wax-coated ball out of the five placed on the monument, as well as a bundle of incense, two torches, and bouquets from the sepulcher. In return, the said rector or curate shall conduct a procession with the Blessed Sacrament on the morning of Easter Sunday, taking it from the sepulcher and carrying it through the square and around the cross under a canopy, with lights in front, which shall be provided by the churchwardens."

The Arrival of the Train in Alboraya

The changes that took place in Alboraya throughout the 20th century were largely driven by urban growth and development. Regarding major metropolitan infrastructures, the Valencia-Sagunto section of the Valencia-Tarragona railway line (now part of Renfe) was inaugurated in 1862. In 1888, the Aragón Station opened, serving the Valencia-Zaragoza line (known as la vía Churra), although Alboraya did not yet have its own station. Around the same period, a railway line was built to transport materials for the construction of the Port of Valencia. The section of the cur trenet (tiny train) railway between Valencia and Alboraya was put into operation on March 17, 1893, and later that same year, the line was extended to Rafelbunyol (José Luis Miralles).

Around 1800, the original urban center of Alboraya extended from the church toward the north and northeast, slightly beyond what are now Molí, Cabañal, Nou, and part of Milagrosa streets. The cemetery was located to the south, which limited urban expansion (Joan Dolç and Vicent Hurtado). In the 19th century, the cemetery was relocated, allowing for the first developments toward the south. The town also expanded westward, northward, eastward, and northeastward, into what are now Cervantes, Miracle, San Pancracio, and Tavernes Blanques streets.

During the first third of the 20th century, streets such as Almàssera, Degà Sanfeliu, Nou d’Octubre, Hermanos Benlliure, and Salvador Giner took shape. Sant Cristòfol and Colón streets marked the northern and eastern urban boundaries until the 1950s (Hermosilla, Rodrigo, Martínez, and Noguera). By the early 1900s, with the Alboraya station already in place since the 1890s, the town expanded further, reaching this key transportation hub. Additionally, at the beginning of the century, a row of houses was built following the railway tracks west of the station, along what is now Canónigo Julià Street.

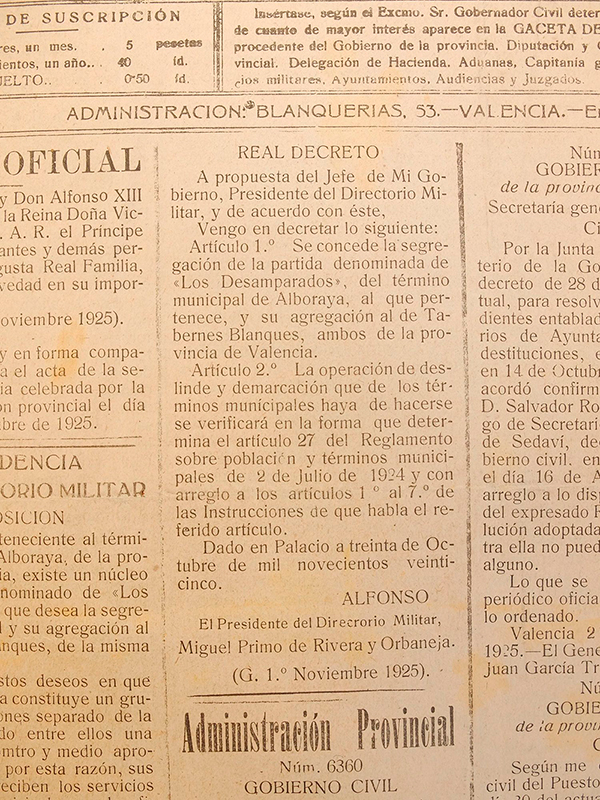

Transfer of Land to Tavernes Blanques

Another significant event in Alboraya's history was the transfer of farmland to the Parish of Tavernes Blanques in 1902. This area, located between the urban core and the Carraixet Ravine, covered approximately 150 fanegadas of land- which equals 12.45 hectares or 30.75 acres. Later, on October 30, 1925, a Royal Decree formally transferred these lands in the Desemparats area to the municipality of Tavernes Blanques.

Port Saplaya and La Patacona

Alboraya experienced major urban transformation starting in the 1950s. During the 1960s, new residential areas were developed, such as Nou d’Octubre Street, the Rey en Jaume and San José Obrero neighborhoods, the southern part of Botánico Cabanilles, and El Palmaret. Other expansions included Port Saplaya, the Pintor Sorolla complex, and the Vera residential area, which emerged from the repurposing of part of an industrial zone. Additionally, Campo de Mayo was developed, along with areas now partially occupied by the Palmaret industrial park. Today, efforts are being made to expand urban development toward the Carraixet Ravine to balance the historic center, which remains concentrated in the northern part of Alboraya.

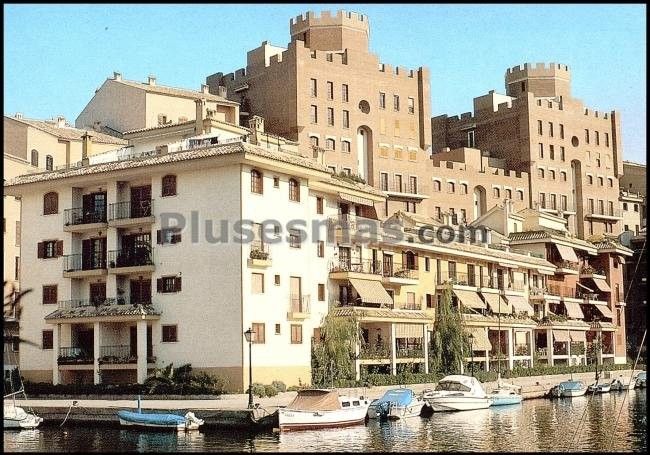

PORT SAPLAYA: Port Saplaya is a coastal neighborhood that was developed as a residential area in the 1970s, located north of Alboraya along the Mediterranean Sea. The first registered residents date back to 1975. Initially conceived as a vacation and second-home destination, it has gradually become a primary residence for many. However, its population still surges during the summer months.

PATACONA: La Patacona is a residential area situated at the southern end of Alboraya, adjacent to Valencia’s La Malvarrosa neighborhood. It features an extensive beachfront and is considered a natural extension of Valencia’s Malvarrosa Beach. Among Alboraya’s urban expansions, La Patacona is the most recent, having been built over the former Vera industrial zone. Since the mid-1990s, residential developments have progressively replaced old factories. As a result of this growth, Alboraya’s municipal government has continuously expanded local services. By the end of 2023, La Patacona had a population of 5,589 residents (INE).